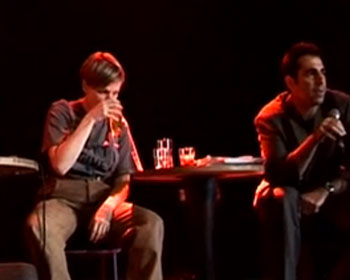

Two men sit at a table, sipping coffee and talking fitfully about art. The man on the right is thoughtful and anxious, wondering aloud what art is and whether he can legitimately call himself an artist. The man on the left, a more sceptical and irreverent character who has, apparently, little interest in either of those questions, tries at first to reassure his companion but soon loses patience and finally throws a glass of water in his face.

Two men sit at a table, sipping coffee and talking fitfully about art. The man on the right is thoughtful and anxious, wondering aloud what art is and whether he can legitimately call himself an artist. The man on the left, a more sceptical and irreverent character who has, apparently, little interest in either of those questions, tries at first to reassure his companion but soon loses patience and finally throws a glass of water in his face.

Maybe when Daniel Devlin was planning his re-enactment of Bas Jan Ader’s Fall at the Serpentine, as when we see him riding his bike along the path beside the lake past some passers-by he does the unexpected and continues his ride by steering the bike straight into the lake, for a split second of decision-making he did not know what would happen. At the moment of confrontation, or rather just before it, is there a way out and for how long is the option available to turn back and say it doesn’t work, I can’t do this, I can’t follow this act through, and to accept instead the disappointment of failure. The instinctive reaction of avoidance is subverted by an act that is both comical and ridiculous.

If you look beck at the 1970s, I mean, they reacted to all these Greenbergian Formalist ideals, and you know, art … well art had become alive, art had become action. It wasn’t made out of the stale droppings left behind by artists, you know, art was … well art was shitting!

![Conversation about art [2005] (HR) Conversation about art [2005] (HR)](https://old.susakpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/croatian_conversation.jpg)

![Conversation about art [2005] (AU) Conversation about art [2005] (AU)](https://old.susakpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/austrian_conversation.jpg)