Art On The Island

by Tomislav Brajnović

Not that long ago I attended a lecture by Miško Suvaković (a contemporary aestheticist, art theorist and conceptual artist who teaches Theory of Art and Theory of Culture in Interdisciplinary Postgraduate Studies at the University of Arts in Belgrade) where he talked about value in art, and how mechanisms for its valuation have developed throughout history. He began the lecture by comparing works of art, identifying which ones were more or less valuable and discussing how we recognise and value them.

At the end of the lecture I asked him if art is something that can’t be valued quantitively – something either has art value or it hasn’t. And if something is considered to be art, you can’t say it has more or less art value compared to another work. Obviously I’m talking in terms of spiritual and immaterial value.

I asked him if he thought art could exist outside the art historical value system and if something being recognised as art is all that is required to gain value as art? He gave the conventional answer you would expect from an art historian: “Everything is subject to different points of view and conventions, and art value does not exist outside of it.”

Maybe we were not talking about the same thing – I was referring to the idealised concept of art – an intrinsic spiritual quality that exists even if the work is not seen and/or recognised, and that exists outside the accepted aesthetic value system (a system which is completely wrong because it is based on material value relating to the work itself and doesn’t consider the artist’s ethical view of the world and the influence of other art in creating the formative context in which we are immersed and which led us to destruction and to the brink of extinction).

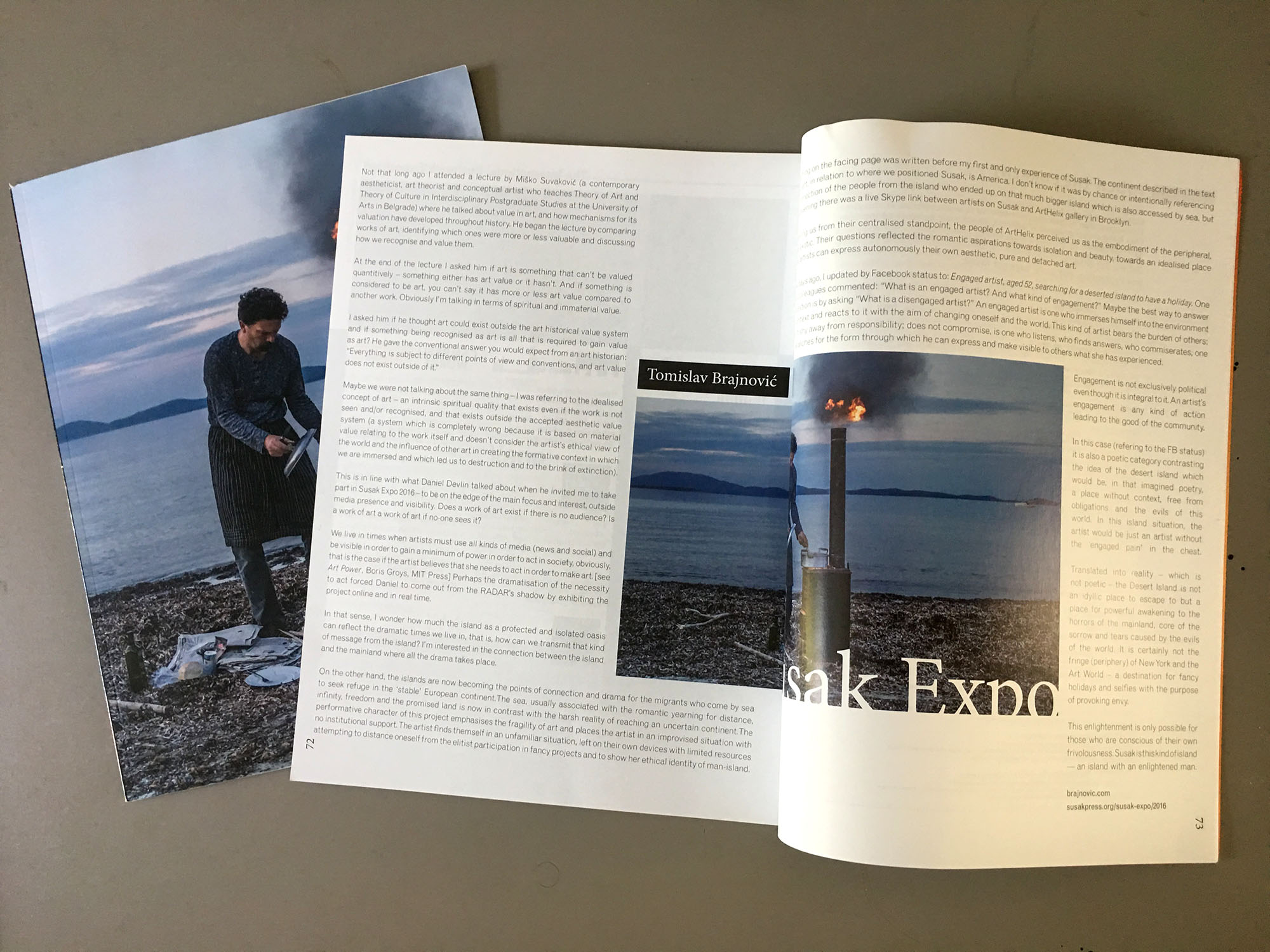

This is in line with what Daniel Devlin talked about when he invited me to take part in Susak Expo 2016 – to be on the edge of the main focus and interest, outside media presence and visibility. Does a work of art exist if there is no audience? Is a work of art a work of art if no-one sees it?

We live in times when artists must use all kinds of media (news and social) and be visible in order to gain a minimum of power in order to act in society, obviously, that is the case if the artist believes that she needs to act in order to make art. [see Art Power, Boris Groys, MIT Press] Perhaps the dramatisation of the necessity to act forced Daniel to come out from the RADAR’s shadow by exhibiting the project online and in real time.

In that sense, I wonder how much the island as a protected and isolated oasis can reflect the dramatic times we live in, that is, how can we transmit that kind of message from the island? I’m interested in the connection between the island and the mainland where all the drama takes place.

On the other hand, the islands are now becoming the points of connection and drama for the migrants who come by sea to seek refuge in the ‘stable’ European continent.The sea, usually associated with the romantic yearning for distance, infinity, freedom and the promised land is now in contrast with the harsh reality of reaching an uncertain continent.The performative character of this project emphasises the fragility of art and places the artist in an improvised situation with no institutional support. The artist finds themself in an unfamiliar situation, left on their own devices with limited resources attempting to distance oneself from the elitist participation in fancy projects and to show her ethical identity of man-island.

Everything on the facing page was written before my first and only experience of Susak. The continent described in the text to the left, in relation to where we positioned Susak, is America. I don’t know if it was by chance or intentionally referencing the connection of the people from the island who ended up on that much bigger island which is also accessed by sea, but every evening there was a live Skype link between artists on Susak and ArtHelix gallery in Brooklyn.

Observing us from their centralised standpoint, the people of ArtHelix perceived us as the embodiment of the peripheral, of the exotic. Their questions reflected the romantic aspirations towards isolation and beauty, towards an idealised place where artists can express autonomously their own aesthetic, pure and detached art.

A few days ago, I updated by Facebook status to: Engaged artist, aged 52, searching for a deserted island to have a holiday. One of my colleagues commented: “What is an engaged artist? And what kind of engagement?” Maybe the best way to answer her question is by asking “What is a disengaged artist?” An engaged artist is one who immerses himself into the environment and context and reacts to it with the aim of changing oneself and the world. This kind of artist bears the burden of others; doesn’t shy away from responsibility; does not compromise, is one who listens, who finds answers, who commiserates, one who searches for the form through which he can express and make visible to others what she has experienced.

Engagement is not exclusively political even though it is integral to it. An artist’s engagement is any kind of action leading to the good of the community.

In this case (refering to the FB status) it is also a poetic category contrasting the idea of the desert island which would be, in that imagined poetry, a place without context, free from obligations and the evils of this world. In this island situation, the artist would be just an artist without the ‘engaged pain’ in the chest.

Translated into reality – which is not poetic – the Desert Island is not an idyllic place to escape to but a place for powerful awakening to the horrors of the mainland, core of the sorrow and tears caused by the evils of the world. It is certainly not the fringe (periphery) of New York and the Art World – a destination for fancy holidays and selfies with the purpose of provoking envy.

This enlightenment is only possible for those who are conscious of their own frivolousness. Susak is this kind of island — an island with an enlightened man.

Leave Comment :